Righteous Among the Nations

“Whoever saves a life, saves the whole world.” The title Righteous Gentile was created by the State of Israel in 1953 in order to honor the memory of non-Jews who helped endangered Jews during the Second World War. In order to be awarded this title, the rescuer must not have demanded any reward in exchange for the help given. In addition, rescued persons or archive documents must vouch for the rescuer. The persons recognized as Righteous Gentiles receive a medal from Yad Vashem with a certificate of honor, and their names are inscribed on the honor wall in Yad Vashem's Garden of the Righteous (Jerusalem). In 2006, more than 21,000 persons had received this distinction.

The first Sister of Sion to receive this title in 1989 was Denise Paulin-Aguadich (Sr. Joséphine), who was an ancelle during the war. Since then, six other sisters of the congregation as well as one brother of the Religious of Our Lady of Sion have received the same sign of gratitude posthumously. They worked in Grenoble, Paris, Antwerp, and Rome. The activity of these sisters and brother who rescued Jews during the Second World War deserves to be remembered. And there are others who, each in his and her place, worked in the same sense, even of they have not (yet?) been given official recognition.

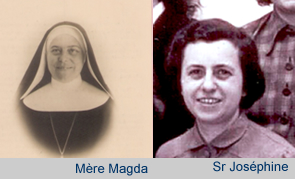

Grenoble: Mother Marie Magda (Marthe Zech) and Sister Joséphine (Denise Paulin-Aguadich)

Marthe Zech was born on September 24, 1879 in Soignes (Hainaut, Belgium) to a family with eight children. She had a twin sister, Madeleine, who also entered the congregation and received the name of Mother M. Guillaume.[1] Mother M. Magda made her first vows in 1908, four years after her sister. She was called to a life of much traveling: Prague, Istanbul, Marseille, Tunis... From 1936 to 1938, she was in Oradea Mare (now Romania), and from 1938 to 1940 in Strasbourg as the first assistant. When the city was evacuated at the beginning of the war, the Strasbourg community had to disperse: one group found refuge in Gérardmer, which was very close; another, led by Mother Odile, left for Grandbourg; while a last group, led by Mother Magda, left for Grenoble to found a new house. They arrived there in September 1940. Denise Paulin (Sr. Joséphine) was much younger. She was born in 1913 and made her vows as an ancelle[2] on April 26, 1940. So she was 27 years old at that time. She was already sent to Grenoble in September 1940. There, the new community's living conditions were not easy. The sisters lived in a separate house, in the Villa Truchetet, which they could acquire and rearrange thanks to the parents of one of the sisters. Already at the beginning of the 1940 school year, they decided to open a boarding school. But very soon the villa became too small: there were some sixty registered pupils already in the first year. Among them were some girls from Alsace who had followed the sisters from Strasbourg. Thus the community was forced to rent one and then several supplementary apartments. This made it necessary to go back and forth more, but it had the merit of facilitating rescue activities. For one month, the sisters lived under precarious conditions, sleeping on straw mattresses, some in the chapel and others in classrooms. Each room was used for several purposes. For example, three times a day, the sacristy became a dining room, and in between, it was the principal's parlor or a room for private lessons. At night, it was a bedroom for one of the sisters. The lay teachers had their dining room and staff room in a small building that had contained hutches, and classes were held in a bathroom in which stood an old four-footed bathtub from the year 1900![3] Mother Magda as superior, Sr. Joséphine as social worker and the boarding school's nurse, as well as others such as Mother Théodore and Sr. Ignace (Anne-Marie Van Hissenhoven, another ancelle from Antwerp, Belgium) each did what she could to help the Jews. Grenoble was then in the free zone; the city and its surroundings had thus become a kind of refuge for endangered people from the occupied zones, and this was all the more possible because until 1943, the prefect of Isère applied orders “without much conviction”, which finally resulted in his being dismissed and then deported.[4] In spite of this, there was a very violent roundup in the city in August 1942; Sr. Joséphine spoke of it in detail in her journal before she stopped writing this for an unknown reason. Finally, it must be noted that after November 1942, the zone was under Italian occupation, which was important, since the Italian army as a whole was not very much in favor of the antisemitic persecutions. Thus Jacqueline Mizné, an internal student at the boarding school, was rescued thanks to Mother Magda, Sr. Joséphine, and the Italian captain responsible for the sector. The latter went so far as to free the little girl, who had been put under house arrest in her home and whose parents were taken. This captain knew Sion through his sister, who had been educated in the Rome boarding school and had good memories of it. He was thus favorably influenced when he recognized Mother Magda's habit. In addition, it seems that the Gestapo had arrested the Mizné's without notifying the Italian police, which annoyed the captain and pushed him to free the little girl and to give orders that the same be done for her mother (at the time of the Liberation, the Mizné family was reunited). The rescuers' activities consisted in furnishing false identity cards and food, hiding girls among the boarding school students, contributing towards finding places in surrounding farms for children whom two Jewish social workers, Ethel and Colette, went to get in Paris, or helping people to go on to Switzerland. Ethel and Colette criss-crossed the countryside searching for families who would welcome or hide children. The sisters also worked with Germaine Ribière[5] as well as with organizations such as the OSE[6] or a clandestine group that came forth from the Eclaireurs Israélites de France [French Jewish Scouts]. Sr. Joséphine knew many people and knew perfectly how to use this network, which extended from a neighbor, Isaure Luzet[7], the so-called “Dragon” who was a pharmacist, to her own parents, Mr. and Mrs. Paulin in Chapareillan, not to mention the friends she had at Notre-Dame de l'Osier, a township close to Grenoble, where many Jews as well as people in the resistance could find refuge. Sr. Joséphine also belonged to the Combat resistance network. There are many testimonies regarding everything that was done.[8] However, let us cite here the names of Jacqueline Mizné, Hélène Kalmus, Rita Verba (who was hidden under the name of Marguerite Sturm), Suzanne Erbsman…Rachel Levy, a little girl who was hidden in the boarding school. Mother Théodore concealed her behind her back, affirming at the same time that the child was no longer in the house. When the Germans came to search, Mother Magda, who spoke German fluently, was responsible for delaying the soldiers as much as possible, while the little girls went over to the neighboring Redemptorist Sisters. Once, one of them was sheltered in the infirmary “because she had caught a very contagious disease”. Everything that was done remained a secret. At times, the Jewish children who were passing through were said to be Protestants, which explained why they didn't go to the chapel. Few people knew what was happening, to the extent that some people were astonished that these children did not know the Our Father... There was also, of course, the problem of the yellow star. Sr. Joséphine remembered that one of the children had kept the star. She had taken it off, but one could still see the mark of it on the garment, and the child had to put her pullover on inside out so as to hide it... She ended her account of what she remembered thus: “That mark was like a symbol of the unforgettable imprint of suffering and fear that remained for ever in the soul of each one of them.” One sister from Grenoble, Sr. Eliezer, was of Polish-Jewish origin. One morning after a night of roundups, men in civilian clothing came to get her using her secular name. According to what several sisters remembered, Mother Magda was called, and she responded by saying that she knew no one by that name. The officers in charge of the investigation said they would return after verifying the name. Following this, Sr. Eliezer was hidden with the Redemptorist Sisters, who had a house opposite Sion, and she could be rescued. The investigating officers never returned. Thus, what happened to Sr. Gila, arrested at Issy- les-Moulineaux and deported, could be avoided in Grenoble. The parish priest of the neighboring parish was Fr. Jaquet. He had arranged a loft where a few endangered people or those waiting for papers could live, but this was only possible for a few days. During those days, theancelles discretely brought food when they went to church. On the left, a certificate with the title Righteous Gentile (here, that of Mother Magda, conserved by Xavier Zech, Mother Magda's great-nephew). On the right, the Truchetet villa in Grenoble. Sr. Joséphine had to leave Grenoble in 1943, as her activities began to be too well known. In the following chapter, we shall encounter her again in Paris. At about the same time, Mother Magda received an obedience for Grandbourg, and she remained there until her death in 1947. She was replaced in her role as superior of Grenoble by M. M. Clotilde. She received the title of Righteous Gentile in Antwerp in 1993. Starting in September 1943 with the surrender of the Italians, the zone was occupied by the Germans, and the last year before the liberation was particularly harsh. During that period, the sisters in Grenoble decided to ask the OMI Fathers (Oblates of Mary Immaculate) for asylum at Notre Dame de l'Osier and to move part of the boarding school there, as the city was becoming too dangerous after a gun powder explosion in one of the city's barracks. Sr. Jeanne-Simone (Lugand) then replaced Sr. Joséphine. The difficulty she had to face in her activities was even greater because of the fact that she was not an ancelle and thus did not have the same freedom of movement as her fellow sister, all the more so as she wore the religious habit. She made her perpetual vows on September 8, 1943, just at the time when the region was occupied by the Germans. She could not make the usual retreat before her vows, as the people needed her and it was a matter of life and death. Sr. Jeanne-Simone wrote in the testimony she sent to Sr. Anna-Maria: “As I re-read what I just wrote, I can't sense the atmosphere of fear and of intense work that really existed. I don't know how I could develop in the midst of so many worries and problems, with the constant threat of the Gestapo. Because our phones were bugged, someone kept watch at the end of the private path that led to our house, we had relatives who worked in the resistance, there were parents of students who were in favor of the occupier (…).” Sr. Jeanne-Simone died at Saint-Gratien on August 4, 2005.

Note on the Ancelles: The congregation of the Ancillae (Servants) of Our Lady, Queen of Palestine, was created in 1924. It resulted from the meeting of a few young women with Dom Pirro Scavizzi, the spiritual director of one of them; these women were animated by a strong attraction to a missionary life. With the support of the patriarch of Jerusalem, they left for the Holy Land and founded the congregation, giving it the name of the sanctuary situated between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, near which they could live. Their vocation was the direct apostolate towards Muslims and Jews in the Holy Land. The new congregation gradually grew and set itself up in Rafat, Jerusalem and Pavia, where it opened its novitiate. Through the mediation of the patriarch of Jerusalem, a strong link was formed between the ancelles' congregation and that of Our Lady of Sion, whose superior general at the time was Mother Marie Amédée. In 1936, it was decided to integrate the ancillae in the congregation with the name “Ancelles of Our Lady of Sion”. The Ancillae could choose to enter Our Lady of Sion or not; most of them did enter. One of them became a contemplative in Sion instead of entering as an ancelle. The few who remained entered other congregations. Although this new branch was fully part of the congregation, its way of life was different to that of the other sisters in apostolic life. For example, the ancelles wore secular clothing outside of the convent and were called “Miss” by the lay people whom they encountered, because their religious state was to remain a secret outside of the convent. Within the congregation, they were called “Sister”. Thus, if a text speaks of “Sr. Marie X.” it can mean either an ancelle (a choir sister or a lay sister) or a lay sister, either a novice or a sister in temporary vows. If the text speaks of “Mother Marie X.”, it is always referring to a professed choir sister who was not an ancelle.). In 1964, the general chapter of the congregation decided on the juridical separation of the ancelles and Our Lady of Sion. The ancelles then formed an association, which they called Pax Nostra. The former ancelles could choose between remaining in the congregation and entering Pax Nostra.

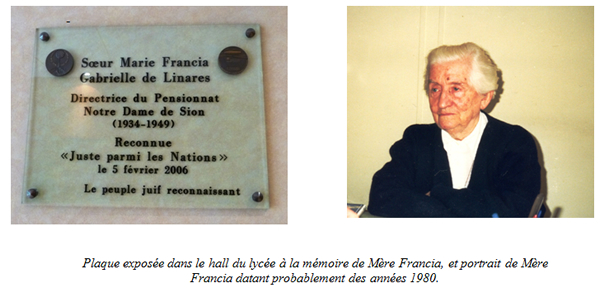

Paris: Mother Marie Francia (Gabrielle de Linarès) and Sister Agnese Maria (Emma Navarro)

Gabrielle Gonzalès de Linarès was born in 1898 to a family with many children, and she was always very attached to her family. She made her first vows in 1928, and her first obediences brought her to Strasbourg, Bucharest, and Le Mans. In 1934, she was sent to Paris as principal of the boarding school and from 1941 on, as first assistant. At her funeral Mass, one sister said of her: “When you didn't know her, you thought she had a severe manner, but when you approached her, you discovered a woman of great kindness who was attentive to what you told her, who listened with her heart (…) She was also a precious help to the students' families, seeking to understand them, to help them, even to assist them when they were in need.” At the time, the Paris convent was very large: around 126 sisters, without counting the general council. There were about 400 students in the boarding school. Sr. Agnese (Emma Navarro) was an Italian of about the same age: she was born in 1900, and from 1930 on belonged to the first ancelles, which meant that she lived in the Holy Land from 1931 until 1934 and again from 1936 until 1937, the year in which she made her vows in Our Lady of Sion. In 1938 she was called to Paris. There, together with another ancelle, Sr. Gabriella Londei (who later was sent to Marseille), she founded what was called the “Marais Center”, the Marais being the Jewish quarter in Paris. This center was a place where children came to study or to do their homework, to take some courses such as household courses, to consult books in the library, etc. Every summer, vacation camps were organized in Grandbourg. Quite quickly, the news spread by word of mouth, and many children came. When the war broke out, Mother Francia as well as Sr. Agnese quite quickly became aware of the danger threatening the Jews, for there were many of them both in the boarding school and in the Marais. These sisters' activities were quite close to that of the sisters in Grenoble: again, it was a matter of hiding children, of giving them false identity cards, and eventually of enabling them to flee from Paris. Like in Grenoble, it was impossible to act alone, and they received the help of social workers (for example Miss Hue, who got them counterfeit papers and looked for placements for the children), of priests (Father Devaux, a priest of Our Lady of Sion, who also received the medal of Righteous Gentile in 1996), of Mother Francia's cousin, of the cousin's concierge , the cousin's doctor (who gave the necessary documents for sending children to safe places “for reasons of health”, certificates that the community's doctor refused to give), and of many others, including once again Germaine Ribière and Fr. Chaillet.[9] At Sion, Mother Francia didn't really have such a team of people who were willing to help even to the end. For she recounted that she was only sure of four sisters[10] and that she kept the others more at a distance, as they were already very busy, and above all, because she was afraid of gossip by sisters who were not aware of the danger. Here as in Grenoble, quid pro quos made it possible to save sisters. Mother Francia told Sr. Anna-Maria that policemen came one day with a list beginning with “Madame Adra”. In all good faith, she could say that she knew no one by that name. Only later did she realize that this was probably Sr. Andrea-Maria, an ancelle who worked with Sr. Agnese at the Marais Center. But the list that followed also contained the names of children who were hidden in the boarding school. Mother Francia recounted that she answered with great assurance: “It is true, they are here, but there is nothing you can do; I won't give them to you. Take me if you want, but never the children.” The policeman ended up leaving and does not seem to have returned. In any case, Mother Francia had taken precautions and sent the children to be hidden with other people, including the Dominican Sisters in Montligeon. Among the children on that list were Janine and Paulette Bitchatch (students at the boarding school since before the war) and Geneviève Lang. They were rescued. Geneviève was sent to a Paris family whom she knew, and they claimed she was a relative from the provinces. In March 1943, Geneviève again came to Sion and remained there until the end of the war. She then was re-united with her mother and her sister (who had been hidden at Our Lady of Sion in Lyon). Her father never returned from deportation. In her testimony, Geneviève emphasized the fact that she never felt the least bit of pressure to be baptized and that she did not hear hurtful comments at Sion (she wore the yellow star), which was in contrast to the private course to which she had gone previously. In hindsight, Mother Francia thought there were people among the police who helped her, even if she never knew who these were. At the Marais Center, people came to seek advice and to entrust to the people there what was most precious to them, including children. Miss Hue, a social worker who, as we saw, also worked with Mother Francia and Father Devaux, got false papers for the children's families. Here is an extract from what Sr. Agnese told Sr. Anna-Maria: “Little Anna's father had told us: 'I am entrusting my daughter to you.' He had lost his wife, and I think one of his sons had been taken (…). We had made counterfeit papers (…). One day, children came to us and told us: 'Miss, they have taken Anna's father.' I was very upset because after that, the concierge arrived with a piece of paper on which was written, 'Miss, Anna now has only you in the world. From now on, you are her father, her mother.' When the father was taken, he had asked to go and get some things, and that is when he had written this message. In what followed, I hid the little girl with the Sisters of Bon Secours.' One day, she answered the Gestapo, who was threatening her on the phone: If I took the little girl, it was in order to rescue her, not to give her up.'” Sr. Andrea-Maria, who was also an ancelle, went to get the children, she accompanied people to the station, and ensured that food tickets kept coming. This generated a large correspondence, which arrived at 61, rue Notre-Dame des Champs, which probably explains why the police were looking for her. But all was not sad. For example, Sr. Agnese also recounted: “We had magnificent feasts (…). We played the story of Esther. We had costumes that Mother Amédée had lent us.” Every summer, she continued to bring the children to vacation camps in Grandbourg. The Evry house journal even recounts that the children went to play in the swimming pool there.[11] After September 1943, Sr. Joséphine was called to Paris, where she first assisted and then replaced Sr. Agnese as director, because there had to be a French social worker so that the center could be recognized as a “Social Center”. At the end of the war, Sr. Agnese remained in Paris for a while before being sent to Rome, where she continued the work she had begun in France by opening a dopo scuola [“after school”] close to the Roman ghetto. She remained there until her death in 1998. The medal of Righteous Gentile was awarded her in 2010. Sr. Joséphine remained in Paris until 1953, when she left the congregation and married. She died in 2010. She was the first of the Sisters of Our Lady of Sion to receive the title of Righteous Gentile (in 1989). Yad Vashem's attention was drawn to her through Mrs. Isaure Luzet, who affirmed during the ceremony in which her own medal was awarded that she could not have done anything without Sr. Joséphine.

Mother Francia finally spent a few years in Paris, then in Saint-Omer, before she was named superior of the ancelles (1951-1959), and then sent to Spain to found a new Sionian insertion. When she returned to France in 1964, she remained in Paris until 1980, and was then sent to Issy-les-Moulineaux, where she died in 1992. The medal and diploma of Righteous Gentile, which were awarded her posthumously in 2006, are now shown in the lobby of the school she directed for such a long time and where she rescued the children, rue Notre-Dame des Champs in Paris.

Antwerp (Belgium): Mother Marie Dora (Anna Otto)

Anna Otto, the future Mother M. Dora, was born on March 29, 1874 in Brussels. Like Mother Magda, she had eight brothers and sisters, several of whom entered religious life. One of her sisters made profession at Our Lady of Sion under the name of Mother M. Stéphane. Anna entered the novitiate in 1898 (she made her first vows on February 4, 1900), and she was called many times to be superior of a house: at Roustchouk in Bulgaria for six years, then for four years in Galatz, before being named superior of Saint-Omer in August 1938. In her menology[12] we can read that “what struck one above all in her physionomy was her kindness; every pain brought her suffering, and she knew how to be maternal with each person; at the same time, she remained firm where keeping the rule and the religious spirit was concerned.” Kindness is also what the former students of Saint-Omer and Antwerp remember about her. Starting at the end of 1939, alarms became ever more frequent, and from May 1940 on, there was the exodus of the northern populations fleeing south. The “Sionian Letter” that recounts the war period in Saint-Omer says: “In the whole city, there was nothing but endless convoys, cars laden with mattresses, coming above all from Belgium.” The house welcomed refugees, including many sisters from other congregations. Then came the first bombings, and the buildings of Our Lady of Sion in Saint-Omer were requisitioned to serve as “ambulatories”[13] and to receive the wounded. The Germans entered the city on May 23. Because of the frequent alarms, the dormitories were moved to the basements, and for a while, the basements in the building with classrooms served as public shelters. On August 30, 1940, the Germans occupied the house. In December 1940, the sisters received a notice from the Kommandantur: the next day, Mother Dora had to go to the station with her luggage, since she was Belgian. And really, the next day, she was united there with some one hundred persons, several of whom were other sisters from the city, all of them English, Belgian or Dutch. They were interned in difficult conditions in a school at Troyes: they had to sleep on straw and underwent lack of privacy and of water for washing. But the city's Little Sisters of the Poor came to help the interned with food and pharmaceutical products. Two days later, Mother Dora and several other sisters received permission to be transferred to their houses. Finally, Mother Dora received an order to be repatriated to Belgium and was transferred the beginning of March to Brussels, then to Antwerp. She could finally return to Saint-Omer on May 30, 1941, 5½ months after her departure. Her health, which was already in a precarious state, became even more fragile as a result of this episode. The following year, in February 1942, she received an obedience for the house in Antwerp. M. M. Guillaume, Mother Magda Zech's twin sister, joined her there in August, leaving Evry, where she had been living for eleven years. During the summer, following the big roundups, Mother Dora hid children in the boarding school using false names. This was the case in particular for Lydia Werkendam, who was then seven years old. She recounted that one day during a bombing, the whole convent had left to find refuge in a shelter. One of the sisters who noticed that Lydia was absent, ran upstairs to wake her and to bring her to the shelter. Lydia added that during the entire war, her mother was in close contact with the convent and that “the sisters did the impossible to reassure Mama”. Mother Guillaume gathered in the convent fallen allied airmen who had landed in territory occupied by the Germans. She organized an evasion network for these airmen, but also for those working with the resistance and for Jews who went through France (Grenoble, where her twin sister directed the Sion establishment), then through Switzerland or Spain and Portugal. Probably Mother Dora and Mother Guillaume were helped in their activity by Father Demann, a Father of Sion who was at Louvain at that time. Mother Dora's health was fragile and she did not survive an operation that was carried out on July 7, 1944. She died on September 23, 1944, a few days after the liberation of Antwerp, which occurred at the beginning of the month. She received the medal of Righteous Gentile in 1998.

Rome (Italy): Mother Marie Augustine (Virginie Badetti) and Mother Marie Agnesa (Emilie Benedetti)

Mother Augustine (Virginie Badetti), was born in Istanbul on May 29, 1881. After making her first vows in 1926, she lived most of the time in the present-day Mediterranean province: Turkey, Egypt, Tunisia... In 1942, she was sent to Rome to become superior of the house. She replaced Mother Mariella, who had been called to Saint-Omer in order to follow Mother Dora when the latter left for Antwerp. Mother M. Agnesa was born in Rome in 1902. She was raised in the boarding school of Our Lady of Sion and then studied nursing and theology. Like the first ancelles, her spiritual director was Don Pirro Scavizzi. After making her first vows in Paris on January 20, 1928 and after a short time in Trento, she spent the entire remainder of her life in Rome. At that time, the congregation had a large boarding school on the Gianiculo; this school was closed on the eve of the war. Instead, an orphanage was opened, of which Sr. Agnesa was the first director. The war between Germany and Italy was declared on June 10, 1943, and that same day Rome was bombed for the first time. Since the sisters' house was at the summit of the Gianiculo hill, they could watch “the desolating spectacle (…) of the flames that rose to the sky in a terrifying way”. The events we are dealing with here started on September 8, 1943, when Italy surrendered. Rome was then occupied by the Germans after a battle that was fought in part in the quarter where the house was: a projectile from a canon ball even fell into the courtyard, breaking a window. The first roundups started on October 15. The account that was written at the end of the war on the situation of the Rome house during that period recounts: “At dawn on October 16 (…) it was raining; tight groups of Jewish women, accompanied by their children, crossed the cancelle in the via Garibaldi.” Mother Augustine was willing to welcome them in the convent. Room had to be made to welcome so many people, and cumbersome furniture had to be moved. Luckily, on the first day, most of the people had brought something to eat. Because of the warm welcome that was given them, the women asked Mother Augustine for permission to have their husbands come. Mother Augustine accepted, not without first asking the vicariate for permission. The dining room was then transformed into a room for sleeping, and you constantly had to step over pallets. The entire space, even the smallest, was occupied: the space under the stairs sheltered a family with seven persons. But whole families were thus welcomed, which allowed them not to be separated. The last ones to arrive found shelter in the greenhouse. A bell was installed in the concierge's house to serve as an alarm signal: when it was rung three times, everybody had to run and hide. For example, there was a basement with coal that could hold some fifty persons, but it had only one opening, which was closed by a large oak cupboard; it had no window and no other door. To hide there meant to risk being buried alive. Later, the refugees preferred to hide with neighbors when there was an alarm, since you literally suffocated in that shelter. If the Germans noticed the make-shift beds during one of their searches of the house, it was explained that these were the mattresses of people who had been evacuated, something that was possible, since there were many of them in Rome. Once, a woman wasn't able to get to her hiding place on time, so a sister took off her headdress and put it on the woman's head, and at the same time she gave her a pot to stir. When there wasn't an alarm, people tried to live as normally as possible. Some benefited from the garden by going for walks there or doing some gardening, others worked for the Vatican in exchange for a small payment, going through correspondence regarding the search for prisoners. In order to do this work, they had received typewriters from the Vatican, and they probably also used these to make false papers. The people who were hidden tried to be useful to the sisters in every way, bringing tablets to the sick, carrying buckets, etc. On Saturdays, some gathered together to pray and to read Psalms. Sr. Dora (Rutar) remembered that at her profession in December 1943, the Jewish guests in the community participated in the celebration. Sr. Luisa (Girelli) added: “It was moving because in spite of the danger, the Jews took part with us in a feast that wasn't theirs. They did this in order to show their gratitude.” Father Marie Benoît, a Capuchin who also received the medal of Righteous Gentile, came to visit the sisters several times . It was obviously difficult to solve the problem of getting fresh supplies of food. A sister was responsible for going to the black market, and sometimes women who were hidden came to help her. Probably the men who received payment also gave at least part of their money to pay for their food or they bought it themselves. For food supplies, the sisters asked for and at least sporadically received help from the Vatican. This situation lasted ten months. Luckily, Mother Augustine ended up getting a document stating that the property was protected by the Vatican and prohibiting searches. One day, the Germans nevertheless tried to enter the house. Some of the Jews who were hiding became afraid and tried to flee. They were taken and one of them was tortured. This happened a few days before the liberation of Rome, which occurred on June 4, 1944. Thus they were freed before being sent to the camps. In the end, all the Jews who were hidden at Sion were rescued. There were lawyers, businessmen... among them; some had brought treasures with them, jewels, gold. Everything had been put in a safe place and could be returned to them in its entirety. Mother Augustine was sent to Trieste in October 1945 and remained there for a few years before going to Paris, where she died on November 20, 1949. Mother Agnesa remained in Rome until the end of her life in 1952. Both of them received the title Righteous Gentile in 1999. The sisters who became involved in helping Jews during this time of persecution acted individually. But each one knew on whom she could count in the congregation, in their families, in their surroundings. When asked why they acted as they did, all of them responded by saying that they only did their duty, and moreover that they were not always aware of doing something heroic. To conclude, together with Denise Paulin-Aguadich we can cite Fr. Bromberger: “In the Resistance, courage consisted in remaining in a state of daydream, which allowed us not only to do dangerous things, but also not to know very well what we were doing.”

Céline Hirsch Poynard

Sources : - File of testimonies by sisters or lay people who took part in the activities, mostly in Paris and Grenoble. This file was put together in the 1990s by Sr. Anna-Maria (Gollé). A copy of the file can be found in the archives in Rome, another in Paris. - The “Sionian Letters”[14] recounting the time of the war, written in general around 1945 or 1946 (very few Sionian Letters were written during the war). - The house journals. - The list of professed sisters, which gives indications regarding dates and places where sisters lived. - The menologies, biographies and necrological notes, insofar as these exist. - The documents that belonged to the sisters or their file, insofar as these exist. - A booklet published by Grenoble in 1990 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the house. - The book by Madeleine Comte, Sauvetages et baptêmes, les religieuses de Notre-Dame de Sion face à la persécution des Juifs en France (1940-1945), published by Harmattan in 2001. - The book by Limore Yagil, Chrétiens et Juifs sous Vichy (1940-1944), sauvetage et désobéissance civile, published by Le Cerf in 2005. - An article written by Xavier Zech, great-nephew of Mother Magda and Mother M. Guillaume, as well as some photographs. [1] Mother M. or M.M. means Mother Marie. At that time, all the Sisters of Sion had the name “Marie”, and so when written, it was often abbreviated and orally even dropped. [2] Cf. the enframed text below. [3] On this, cf. the memoirs of a former pupil in the booklet published in 1990 for the 50th anniversary of the Grenoble house. [4] This was Raoul Didkowski, who was prefect from 1940 until August 1943. [5] Germaine Ribière received the medal of Righteous Gentile in 1967. [6] Organisation de Secours aux Enfants [Aid to Children Organization], a Jewish foundation set up in 1912 in Russia and brought to Paris in 1933. [7] Isaure Luzet received the medal of Righteous Gentile in 1989. Among others, she hid the protégés of Our Lady of Sion when a visit from the Germans was announced. [8] For more details, cf. especially Madeleine Comte's book, Sauvetages et baptêmes, and the file containing testimonies collected by Sr. Anna-Maria in 1990 (in the archives). [9] Father Chaillet received the medal of Righteous Gentile in 1981. [10] These were Mother Apollonie, who was the assistant novice mistress at the time, Sr. Martha and Sr. Charline (at reception), and Sr. Lutgarde. We also know that Sr. Marie-Labre and Sr. M. Nazaire helped in the dining room, and that Sr. Hildeberthe, who was from Germany, took “difficult steps” at the Kommandantur (cited by Germaine Ribière). [11] August 10, 1942: Our swimming pool continues to meet with great success, in the morning with the Paris children's camp, in the evening with that of the ancelles.” A distinction must be made between the Grandbourg house and that in Evry. These two houses were situated in the town of Evry, but they were two different communities; one had a boarding school, whereas the other was occupied mainly with a parochial school and with visits to the sick. [12] The small biographies that were written after the death of certain sisters who had led an exemplary or particularly virtuous life or who had held important responsibilities in the congregation are called menologies. These texts (generally of two or three pages) were read throughout the year in the refectory. [13] This was the name given to places that welcomed wounded soldiers and gave them “general” care, but where there were no permanent doctors, in contrast to the military hospitals. [14] These are letters that the communities wrote every three months in order to share news and significant events occurring during the three months with the rest of the congregation. The house journals were notebooks in which, day by day, a sister wrote noteworthy events as well as the community's activities. |

Home | Who we are | What we do | Resources | Join us | News | Contact us | Site map

Copyright Sisters of Our Lady of Sion - General House, Rome - 2011